- How Collaborative and Proactive Solutions Helped Me Deal with My Autism - December 7, 2020

I received my autism diagnosis late in life and while it gave me insight into the challenges I faced, much of the help I needed to deal with my condition came not from the diagnosis but from Dr. Ross Greene’s Collaborative and Proactive Solutions Approach (called CPS) to parenting challenging children (for more information about CPS see Dr. Greene’s Walking Tour for Parents. For an in-depth description, you can also read “The Explosive Child”.

I would like to share the top 3 things CPS did to improve my life for the better. While every child with autism comes with their unique needs, I hope that the information about what CPS did for me as an adult will help parents and caregivers of autistic children better understand the things an autistic child under their care might need in order to thrive.

CPS has helped me to:

- focus on the causes of my stress rather than my poor responses to stress;

- realize I am not a bad person;

- accept, rather than resist, freedom from a cycle of increasing expectations.

CPS focuses on the causes of stress rather than the responses to stress

CPS helped me by clearly separating the causes of my stress from my poor responses to stress. For example, autistics have been noticed doing “weird” things like rocking back and forth, playing with a fidget toy, curling up into a ball, flapping their arms around, having meltdowns over the smallest change to a routine, not making eye contact in a conversation, interrupting others when they talk, getting fixated on meaningless details, screaming with explosive rage to minor setbacks, and biting, kicking, punching, pulling hair seemingly without provocation.

CPS regards these “maladaptive” behaviours as signals that the child lacks the skills to meet expectations, and deliberately removes from the conversation dysfunctional behaviours. Instead, CPS moves “upstream” to identify lagging skills expectations that the child has difficulty meeting.

For example, when my children did not respond to my requests to clean the kitchen, I would respond with explosive rage. No matter how profusely I apologized afterwards and tried to do better the next time, the pattern kept repeating. Reminders from experts on how devastating my yelling was on the children did not help much. I also responded defensively to confrontations about my latest tantrum and would go so far as to try and blame it on the kids.

CPS helped me stop trying to listen to advice about my responses to stress and instead look for the causes of stress by identifying my lagging skills. Eventually I learned that I lacked the skill to recognize when I was hungry, tired, and/or upset and needed to come up with better responses such as having a snack or taking a nap or calming myself down from a previous unsettling incident.

I am not a bad person

I do many things that offend and even hurt other people, CPS has helped me to see myself as something other than a “bad person”. I have been told by multiple people that I’m rude, I interrupt, I’m inconsiderate, I lack basic empathy and compassion, that I make everything about me, that I think only of myself, and enter into every interaction with the view of getting something for myself. I naturally concluded that I was a “bad person”. Other autistics who received a diagnosis late in life also report similar things. CPS offered me an escape from this kind of thinking.

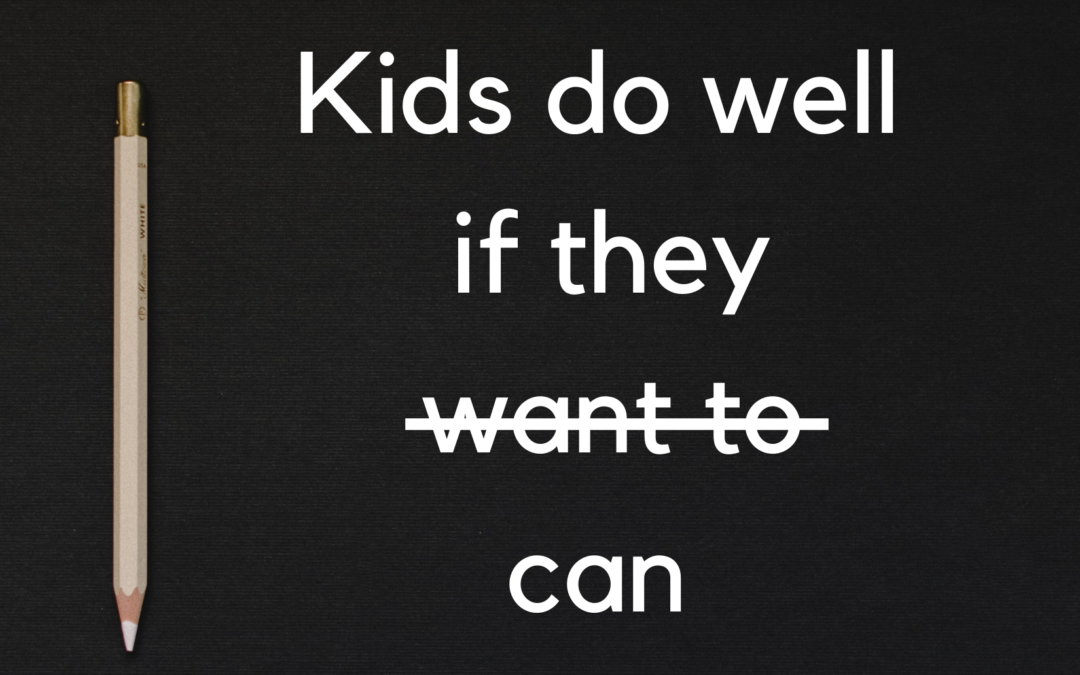

Dr. Ross Greene notes that every punishment, reward, rule, pep-talk, or motivational speech presumes that “children do well if they want to”. Every time someone says “she enjoys doing poorly; he enjoys pushing my buttons; she thinks she can pull the wool over my eyes; he just does not care; she’s not working up to her potential; I know he can do it the effort is just not there,;she needs to wake up; he needs someone to light a fire under him; she’ll have to hit rock bottom before she’ll want to float,” they presume the problem stems from a lack of motivation. Dr. Ross Greene asserts (using evidence gained from something called the Assessment of Lagging Skills that the failure to meet expectations stems from a lack of skills (CPS asserts that “children do well if they can”) rather than a lack of motivation (CPS rejects “children do well if they want to”).

For example, even before I figured out why I (and other autistics) feel the urge to tell a similar story whenever we hear a story about someone’s day or week (Tobey Macguire’s Peter Parker does this repeatedly in Spiderman-3 just before Mary Jane rejects his marriage proposal), I could focus on what is making the conversation difficult for me rather than beating myself up over how much other people hate it when I change topics and make things “all about me”.

Even before discovering the lagging skill underlying the unsolved problem and my explosive or maladaptive behaviour (such as when I say “no, Daylight Savings Time ends in November, it does not start in November”), CPS provides a way to “shift our lenses”. Presuming that I am having a hard time rather than giving people a hard time allows me to see the damage I do to other people through my thoughtlessness as more like the damage done by a safety hazard rather than like the damage done by a malicious predator. While I can live with other people thinking and saying I am a bad person, thanks to CPS I never have to go back to believing I am a bad person.

After identifying their child’s difficulties meeting expectations, caregivers can teach skills or get the child to use different skills to allow them to meet expectations. For example, after I learned that I lack the skill to know when I should go to the bathroom (I only notice when I have about twenty minutes until disaster), through CPS I learned to go upstream to solve this problem easily by always going to the bathroom before doing something that takes me more than twenty minutes away from a bathroom. However, CPS also embraces other responses to unmet expectations…

CPS encourages rather than resists freedom from a cycle of increasing expectations

CPS has helped me accept rather than resist solutions that free me from a cycle of increasing expectations. Although masking or camouflaging behaviours allow people to meet expectations in creative and seemingly equivalent ways, CPS also embraces the idea of dropping expectations in order to remove stresses on a child exhibiting challenging or maladaptive behaviour. While this sounds like “giving up” or “giving in”, CPS encourages people to consider dropping expectations as a way to buy time to discover root causes, or to focus on a more pressing matter. Dropping expectations can also serve as a long-term solution in order to respond appropriately to the hand one has been dealt rather than setting people up to fail by insisting they meet the same expectations that others do. In particular, dropping expectations helped me preserve the mental health that some people on the autism spectrum compromise when they camouflage or mask their condition.

In my case, I have dropped expectations because I find interactions with more than one person highly demanding. I now focus on working my job, spending time with immediate family, meeting friends/extended family one-on-one, getting exercise, and isolating in my apartment. I intentionally stopped attending larger group activities such as parties, group events, and trips out of town even when they involved close friends and extended family. These activities went off the priority list even before COVID and my stress level dropped because of the reduced expectations.

By focussing on things which make it difficult for me to meet expectations instead of focussing on my dysfunctional responses to stress, CPS helped me deal with causes of stress rather than exchanging one dysfunctional response such as yelling for a more socially acceptable but equally dysfunctional response such as sulking.

By presuming that all my inappropriate and harmful behaviours stem from a deficit in skills rather than a deficit in motivation, CPS has helped me to see myself as something other than a “bad person”. CPS has taught me to value responding to the hand I have been dealt more than meeting expectations other people meet. As a result, CPS has helped me to embrace a reduced set of expectations instead of trying to find increasingly convoluted and dysfunctional ways of meeting expectations.

3 ways CPS may help caregivers and parents of autistic children

I hope that reading how CPS helped me will help caregivers and parents better understand and discover what the autistic children in their care might need in order to thrive. In closing, I would like to put forward some ideas that might help the autistic child in your care:

1. By focussing on the conditions that made meeting expectations so difficult, you can take the focus off of fixing us (or stopping the weird things we do) and move towards understanding us. We often do not even understand ourselves and you can give us the precious gift of self-awareness and self-understanding even before you solve any of our problems.

2. By adopting “kids do well if they can” rather than “kids do well if they wanna” lens, you can save us from the all too common tragedy of growing up believing we are “bad people”. Once again, you can do this even before you help us solve any of our problems.

3. By dropping expectations to respond to the hand we are dealt rather than insisting we meet the same expectations that others do, you can save us from the never ending cycle of increasing expectations that comes from every success, coping tool, or creative solution.

In sharing how CPS has helped me deal with the challenges relating to my autism, I encourage caregivers of autistic children to learn about Dr. Ross Greene’s collaborative and proactive solutions approach.

I hope CPS will help you to support autistic children in your care, learn about themselves and eliminate stressors that they might not even realize cause them stress.

Most of all, I hope CPS will help you to teach us that despite our difficulties meeting expectations, we can still see ourselves as good people doing our best to give and receive love, respect, care and understanding.

Photo by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash

Editor’s Note: We purposefully provide the space for people from within a community to choose the terms they feel are respectful to describe themselves and recognize there is a live debate about person-first vs. identity-first language in the Autistic community.

We would love to hear your thoughts in the comments section below.

Recent Comments